Today is the International Day for Women and Girls in Science, and to celebrate, we’re honoured to profile a few amazing ICORD women who offer a variety of perspectives on what it’s like to be a woman in science. Please meet:

- Carson Graham Secondary student Shana George, Indigenous Summer Research student and part-time student assistant in Dr. Corree Laule’s lab.

- ICORD Principal Investigator Dr. Bonita Sawatzky, associate professor in the UBC Department of Orthopaedics. Click here to learn about her SCI research.

- Dr. Elena Okon, research scientist with Dr. Brian Kwon.

- Jessica Archibald, PhD student with Dr. John Kramer, and member of ICORD’s Trainee Committee

- Principal Investigator Dr. Veronica Hirsh-Reinshagen, assistant professor in UBC’s Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, specializing in neuropathology.

- Katlyn Richardson, PhD student with Dr. David Granville, and member of ICORD’s Trainee Committee

- Sarah Morris, PhD student with Dr. Laule

- Nicole Janzen, manager of the Tetzlaff Lab

- Amanda Lee, research assistant for Dr. Andrei Krassioukov

- ICORD Principal Investigator Dr. Lyndia Wu, assistant professor in UBC’s School of Biomedical Engineering. Click here to learn about her lab.

The UN International Day for Women and Girls in Science exists because fewer than 30% of researchers worldwide are women, and globally, female student enrolment in STEM is very low. The goal of establishing this annual day is to promote gender equality in access to and participation in science.

“I’m learning so much”

Shana George

Grade 12 student

When did you know you wanted to be a scientist?

I knew I wanted to be a scientist at the end of Grade 10, starting when a friend and I would compete to see who got a higher mark in Science 10. Since then, the more I learn, the more my love for science expands.

Tell us about the research you are involved in at ICORD and/or PARC.

During the summer of 2019 I worked as a part of the Indigenous Summer Student program at ICORD. I interviewed participants about how PARC affects their physical, mental and social health, and I learned so much about SCI and neurosciences. Since the fall I have been working part time in Corree Laule’s lab. I work with a PhD student so I am learning so much.

Do you face any challenges as a woman in science? If so, how do you deal with them?

I feel that people doubt my intelligence, although I do not pay attention to them much. I just tell myself, “I can do it, failure is a part of the process to success, and I will do anything I put my mind to!”

What’s your favourite thing about being a scientist?

My favourite thing about being a scientist is the fact that scientist are people who can go into a topic thinking “I might be wrong,” and knowing that being wrong can help us learn. That is why I am so passionate about learning, because I know every time I fail or I don’t do well I learn more about myself.

Are there any fields or topics in science that you are hoping to pursue in the future?

I am hoping to be a neurosurgeon in the future, but I have back up plans such as working in the fields of forensics or astrophysics. I know there is so much more science I can explore so it all depends on what I find and who I connect with.

“I was the first woman academic in my department”

Bonita Sawatzky

Principal Investigator and UBC Associate Professor

When did you know you wanted to be a scientist?

I wanted to be a medical researcher after meeting my academic mentor, Dr Judith Hall, who hired me as a summer research student. I met her for another purpose and she later offered me a job. I loved perusing the latest issues of journals in the library and thought, “what would be better than searching through and creating knowledge in medicine?”

Tell us about your career.

My first job in science was to review clinical charts in medical genetics regarding finding patterns in babies born with multiple congenital anomalies that did not fall into specific syndromes. I worked with a geneticist and a paediatrician at BC Women’s. I loved the paediatric component and once this summer job was over I looked again but at Children’s Hospital where they were looking for someone to manage their clinical database. From there, the orthopaedic aspect of my work came to life and I ended up working as the orthopaedics research assistant. Gait labs were becoming in vogue across the U.S. and I took an interest in biomechanics of gait in children. I completed my Masters in Biomechanics at UBC Kinesiology and helped create the first clinical gait lab in western Canada. I was strongly urged by the department to get my PhD so I completed a Inter-disciplinary PhD in Applied Science at SFU involving computer graphics, engineering and orthopaedics. I got my faculty position upon completion of my PhD. I worked in Paediatric Orthopaedics, BC’s Children’s Hospital, primarily doing Gait Analysis and wheelchair propulsion testing. I moved to ICORD to collaborate with others working on spinal cord injury research when the Blusson Spinal Cord Centre opened in 2008. Again, my work has focused on mobility related devices for people with disabilities as well as other spinal cord related projects.

Have you faced any challenges as a woman in science? If so, how did you deal with them?

My main challenge as a woman was often at attending international orthopaedics or biomechanics conferences where the percentage of women was less than 10%. It was hard to be taken serious at times, especially by the older professors/surgeons. I personally did not face much discrimination as a woman, as I was the first woman academic in the department. I had strong support from many members within the department but it was hard to see other women who came later being treated less well.

What’s your favourite thing about being a scientist?

Always learning new things. Life is never dull and boring. There is always something new around the corner and new collaborations. It’s great to meet so many really bright people around the world.

What sort of mentorship or guidance have you been able to offer to younger women thinking of careers in science?

I always have an open door policy for students that want to talk about career ideas and their goals. I have met countless students that explore medicine as an option and then pursue graduate studies instead after our conversations as science/engineering offer a broader range of opportunities.

What advice would you give to young people just starting out in their science careers?

I would say to get a broad range of experiences, meet as many people as you can to learn different ways of addressing problems. Connect and collaborate with others, even when it is challenging to do so because you never know what opportunity may arise from that collaboration. Keep your options open. Find an area that is really interesting to you and that will keep your attention for a while. You need the passion behind to keep you going when the hard work is overwhelming. Research is hard work!

“Be careful! Science is addictive.”

Elena Okon

Research Scientist

When did you know you wanted to be a scientist?

I was born in a southern Russian city. My parents were teaching in local universities, my older sister and brother studied in school, so I was immersed in talking about science and education from the time I began to hear and understand. There were a lot of books at home, including scientific books, and reading them often was my entertainment. So there were no alternatives to a career in Science.

Tell us about your career.

I graduated in 1972 from the Institute of Biophysics of the Russian Academy of Sciences. At that time, the double helix, nerve impulse and chemiosmotic theory of ATP synthesis had only recently been discovered, and ion channels in the cell were discovered during my graduate studies. I received my Ph.D. and stayed after graduation in the same laboratory and worked there for years as a research scientist. My research was related to tissue respiration and effectiveness of mitochondria reactions.

At the end of the 80s, during a crisis in Russia, funding for research practically stopped, and my husband and I had to look for a way to continue our careers in science. Eventually we found jobs at UBC. I was fortunate to get a Research Associate position studying vascular dysfunctions in pathology and diabetes. I worked in this very interesting and important field for about 10 years and was lucky enough to find some interesting results. After the head of the laboratory retired, I got a position in Dr. Brian Kwon’s laboratory at ICORD. I was very interested in neuroscience, and intrigued by the mystery of why there cannot be regeneration in the central nervous system. Finally, after a long career in Science, I will retire this spring.

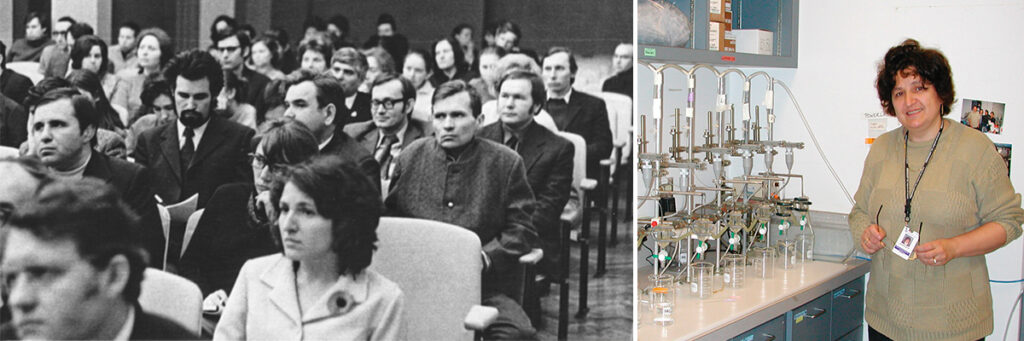

L: Elena attending a conference at the Institute of Biophysics in the early 80s; R: Elena at work at the Heart and Lung institute in 2003.

Have you faced any challenges as a woman in science? If so, how did you deal with them?

A big challenge for many women in science is being a mother. Science requires devotion, and having children also requires devotion. Each child causes at least a several-month break in work, and when you return, you have to work hard to catch up with the train going with increasing rate. Fortunately, the laws in Russia are on the side of working women, and my boss was a woman with two kids, who well understood my problems. I have two children, and now my daughter also has two kids. She recently defended her Ph.D. thesis in Linguistics.

What’s your favourite thing about being a scientist?

Being a scientist helps you understand the world around you. You can always just feel the pulse of developing science. During my career in science, many important discoveries were made: cell signalling, epigenetics, giant mitochondria, PCR, microRNA, the genome was read . . . Not to mention how scientific techniques and devices have improved and advanced the ability of research. Best of all is when you get some unknown findings, and after a series of experiments you suddenly understand what it is. I was fortunate to have this happen several times in my life. Nothing is better!

If you could go back in time and give your younger self some advice for your career, what would it be?

If you feel that knowledge is your best value, if you are ready to learn each day and be never satisfied with that you’ve already done – this is your way. But be careful! Science is addictive. And I wish you every success in this very privileged career.

“I have some very inspiring role models”

Jessica Archibald

PhD student

When did you know you wanted to be a scientist?

I always had an interest in human body and its health. During my undergraduate studies I thought research had a potential for a greater impact in human health, and I wanted to play a role in that.

Tell us about your studies so far.

During my studies at the University of Guelph, I volunteered at a lab that investigated pain. I performed a literature review on implications of altered brain regions in chronic pain patients, and was fascinated by how little we know about the central nervous system due to the lack of techniques to examine it (non-invasively). This learning experience solidified my goal to research the brain in relation to pain. When the time came, I searched for pain scientists and met Dr. John Kramer. Throughout my MSc, we investigated neuroimaging techniques better suited to provide direct markers of neuronal activation, that is, functional magnetic resonance spectroscopy (fMRS). Now in my PhD, I will investigate the ability of fMRS to provide a better understanding of the neurochemical mechanism of the brain when experiencing pain.

Have you faced any challenges as a woman in science? If so, how did you deal with them?

I have faced challenges, being a woman, which I feel are not exclusive to my professional environment. I have learned to deal with every situation as it comes, and to reach out for support from those around me. It has been very inspiring to work alongside female role models such as Dr. Erin MacMillan and Dr. Corree Laule in the physics department at UBC. Neuroscientists, such as Dr. Schweinhardt and Dr. Michèle Hubli in Switzerland, and previous remarkable post-doctoral fellows in the Kramer Lab Dr. Jacquelyn Cragg and Dr. Catherine Jutzeler.

What’s your favourite thing about being in this field?

My favourite thing about being in this field is the sense of discovery that can come from researching two “separate” fields (physics and physiology) to find a solution, which hopefully improves how we manage chronic pain today.

What sort of mentorship or guidance have you been able to offer to younger women thinking of careers in science or engineering?

I like to think that being a female in science alone can provide evidence for younger women thinking of careers in fields that have previously been considered to be dominated by males. When I mentor students and I aim to share the passion I have for research and help them discover theirs.

What kind of mentorship/guidance would be helpful for you at this stage in your career?

I think the most helpful guidance I am receiving at this stage is opportunities and support in collaborations with other scientists and groups.

“I love that moment when you realize ‘oh, this means something!’”

Veronica Hirsh-Reinshagen

Principal Investigator and Assistant Professor

When did you know you wanted to be a scientist?

I’ve always had a curious mind. I’ve always tended to question everything and had a desire to answer my queries. This desire really crystallized once I finished medical school. I decided that the strictly clinical aspects I had been exposed to in medical school had been enough, and that my passion lies within basic science research. And that’s why I came to Canada – in order to do my PhD in neuroscience.

Tell us about your career. How did you end up working at UBC?

I did my medical degree in Chile and then came to Canada to do my PhD in neurosciences at UBC’s Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine. My mentor was Dr. Cheryl Wellington who is another PI at ICORD. After completing my PhD, I decided to stay in Canada, validate my degree, and do my clinical training. Now that I’m done, I can take on a dual role in both the clinical and research aspects of being a neuropathologist.

When people think of medicine they usually think of patient care, however there are other careers that don’t necessarily see patients directly such as those in public health, epidemiology, radiology, pathology, or microbiology. What I do for a living involves looking at post-mortem material biopsies and forming a diagnosis. By observing histological changes through a microscope, I can detect a tumour or a neurodegenerative disease. I quite enjoy how visual my line of work is. Once I look at all the microscope slides containing brain sections of someone who has passed, I will issue a report for the families stating what condition their loved one had, and how that helps explain what symptoms they had during their life. The rest of the data is then used by basic scientists to correlate imaging, symptoms, and biomarkers with pathology. In addition to this clinical work, I like to do research. It took me a while to find my line of research but I think I finally found it. I am interested in astrocytes, which are a cell type in the brain. There isn’t much known about astrocytes, especially in human brains. There is a lot to be learned about whether there are any subtypes, how they work, and how they change in size.

What’s your favourite thing about being a scientist?

Getting answers. I still remember when I was in Dr. Cheryl Wellington’s lab and I got my first positive result on a Western Blot, which actually answered something. I love that moment when you realize “Oh, this means something!” It does take a long time to get an answer. It takes a lot of tries and receiving lots of false positives and negatives. But when you truly get that one answer that you can then further unravel to understand more, it’s extremely gratifying. Another thing I enjoy is to see what other people have done — to see how we have advanced the field and get a sense of where we are currently at in terms of knowledge.

What sort of mentorship or guidance have you been able to offer to younger women thinking of careers in science or engineering? Or have you had any valuable female mentors throughout your career?

Copies of her PhD thesis!

I don’t think I’ve been a bonafide mentor to anyone just yet but I have had some teaching interactions and some guidance where I’ve guided small projects. In terms of my experience being mentored, I learned a ton from Dr. Wellington who was a fabulous mentor. Like myself, she also studies neurosciences in the Department of Pathology. When I was in her lab, we researched lipid metabolism. However, nowadays I believe that’s a little bit less of her focus and that she has shifted more to studying biomarkers and traumatic brain and spinal cord injury.

Have you faced any challenges as a woman in science? If so, how did you deal with them?

Yes, I think everyone experiences challenges but specifically as a woman and as a mother, I think that it’s hard to find the balance between doing what you’re passionate about, and having to care for your kids. Finding this balance between being a wife and a mother, and doing what I love has certainly been difficult. Having talked to women who’ve been neuropathologists before me, I do think the landscape is changing so that this balance is made easier. For example, nowadays we have maternity leaves for those who wish to take it. It is also a possibility to share housework and childcare with your husband or your partner. Personally speaking, I’ve been quite supported by my colleagues, as well as by the university in order to really be able to strike that balance. I think a further improvement would be to have more women in science who could be role models and in positions of power. Women in power will be strong leaders by example, while also being able to better protect this delicate balance by saying “That’s okay, take your time, I allow you to do what you need to do”.

What advice would you give to your younger self or to other young people just starting out in their science careers?

Go for it! If you feel like this is what you want to do, go for it. There are so many things to be wary of such as job prospects, or how long the journey will be, potential suffering, student debt loans and so on and so forth. I know that there are many obstacles in the way but if you feel that you’ve found what you like to do then just go for it. The first step and the most important thing is to find an occupation that you believe in and that you feel is worthwhile. And once you’ve found that, go for it. Just follow your gut feeling and the obstacles will solve themselves. If something is what you want to pursue and this is what you believe in, you will be able to. My personal journey has been long and I’m no longer the youngest one amongst my colleagues. However, it’s most definitely been worthwhile.

“I hope to lead by example”

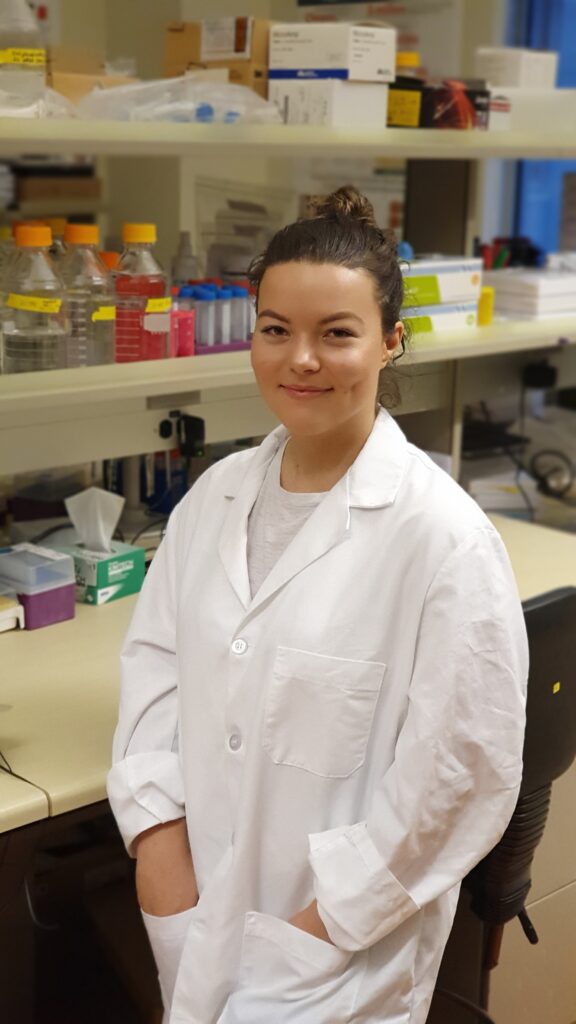

Katlyn Richardson

PhD student

When did you know you wanted to be a scientist?

I think I can trace back my fascination with science as early as elementary school. I had this incredible science teacher, Ms. Hops. My favourite topic was space. She did not teach from a single textbook. If we wanted to learn about it, she taught it to us. In grade 6 she taught us Einstein’s Theory of Special Relativity to answer a classmate’s question. Never have I witnessed a class where students were so excited to learn. After that my fascination for science stuck; albeit some mediocre high school physics classes made me reconsider my fascination with space.

Tell us about your studies so far.

I am in my second year of PhD studies with Dr. David Granville in the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine. My research is currently focused on investigating the role of granzymes in skin inflammation, disease and wound healing. My first encounter with the Granville Lab was while working as an undergraduate research assistant in a lab at the Research Pavilion (next door to ICORD). I was drawn to Dr. Granville’s similar interests in skin research and was excited to explore the idea of a future graduate position in his lab.

Have you faced any challenges as a woman in science? If so, how did you deal with them?

I consider myself to be comparatively fortunate; I have had the privilege of living in a time and place where I was relatively free to pursue my career of choice. That said, there are still obstacles that discouraged me from doing so, the largest being reconciling society’s stereotypes of what it means to be a woman with what it means to be a scientist. Am I less of a scientist because I’m not a nerd or anti-social? Am I less of a woman because I’m not prioritizing family or a caretaker role? It has been hard to find where I fit into these reductive views. Luckily, after surrounding myself with other women in science I have found that this is the case for a lot of them as well, and there’s solace in that. Another challenge that further complicates opportunities for women in STEM is tokenism. When women are hired or awarded for the sake of diversification, it dilutes recognition of true hard work. Remarks such as “they only gave it to her because she’s a woman…” can be just as demoralizing as not being given the opportunity in the first place. These comments are likely to remain unless people are made aware of this issue – perhaps this is a start?

What’s your favourite thing about being in this field?

1. Discovering new things! 2. Being able to solve practical problems that will help large numbers of people.

What sort of mentorship or guidance have you been able to offer to younger women thinking of careers in science or engineering?

Through my encounters with science as a young woman I was fortunate to have had been taught and mentored by women in science. I hope to lead by example, as they did for me, to

allow younger women to envision themselves in a STEM field. In the last few years this included helping to organize a Women in STEM workshop and teaching science as a mentor for initiatives such as Let’s Talk Science, the Research Experience Program and the Advanced Molecular Biology Laboratory Outreach Program, etc.

What kind of mentorship/guidance would be helpful for you at this stage in your career?

I think the most useful guidance for me at this stage would be from women who have managed to raise a family while at the same time pursuing faculty appointments. This is a hurdle I find most intimidating, and one which I hope to overcome in the next decade.

“I think the idea of being a scientist crept up on me”

Sarah Morris

PhD student

When did you know you wanted to be a scientist?

I really liked math in school and would spend more time on my math homework to avoid writing English essays. Taking this as a sign, I applied to do physics, chemistry and math at university. For a long time I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do and which area of science I was interested in. In undergrad I particularly liked chemistry lab experiments, astronomy and theoretical physics and had very varied and vague aspirations: I wanted to be a rocket scientist one day and a marine biologist the next. I think the idea of being a scientist crept up on me, as I kept finding my courses interesting and signing up for more research internships and the next thing I knew I was applying for PhD positions.

Tell us about your career/studies so far.

I did my undergraduate degree and Masters at the University of Cambridge. I wasn’t sure what type of research I was interested in so I tried a variety. I did one summer internship in the Astrophysics department at the University of Oxford, processing images of ultra-luminous infra-red galaxies 5 billion light years away. And then the next year I did an internship at a particle accelerator laboratory, writing software to set up and maximize the momentum of the electron beam.

While I found both of these projects interesting and enjoyable, it was when I started working on my Masters project in MRI research that I felt that I had found the area for me. It appealed to me for many reasons; the physics behind MRI is interesting and complicated, the implementation can save lives in the real world and it is a vibrant research area with new technologies being developed daily. I applied to 6 grad schools for Medical Physics across the US and Canada and chose UBC due to a combination of the excellent MRI research group, the conversations about research I had with Dr. Corree Laule via email, and the location. (I love skiing! And hiking! And beaches!)

Have you faced any challenges as a woman in science? If so, how did you deal with them?

I have mostly been quite lucky and have experienced very little discrimination in my scientific career so far. Medical Physics in particular has a more even gender ratio than some other areas of science and I have been lucky to have lots of female research role models to look up to. One thing I think most scientists (maybe people in general!) deal with to some extent is imposter syndrome. I have sometimes felt particularly unconfident in my own abilities when I am in a situation where my peers and teachers are mostly male. To combat this I try to take note of the insecurity, question where it is coming from and also remind myself that it’s likely that a lot of other people in the room are feeling unsure of their abilities too. Another smaller annoyance I have experienced is the surprised look I sometimes get from strangers when they ask what I do and I tell them I am a Physics PhD student. While I find these interactions awkward, I console myself that I have at least updated in their mind what a Physics PhD student looks like. I think the scientific community as a whole is in the process of becoming aware of many ways gender bias can creep in and I have a lot of hope for the future.

What’s your favourite thing about being in this field?

I like the big collaborative research projects I get to be a part of. Many of our projects involve discussions between MR technologists, disease specialists, radiologists, pathologists, lab technicians, engineers and physicists. I like the variety of my job which involves collecting MRI data, analysing it with a range of software tools, making graphs and figures, writing papers, meeting with other scientists to discuss research, teaching undergraduates and much more. I really like the fact that every day is different and that I have a lot of freedom to choose how I do my research. And finally I like the feeling that I am contributing to something which could help people.

What sort of mentorship or guidance have you been able to offer to younger women thinking of careers in science?

I have had the pleasure of mentoring Shana George from ICORD’s Summer Research program for Indigenous youth. It’s great to get to work one-on-one with young aspiring scientists and it’s been really fun to show her all of the brain and spinal cord MRI data I work with. I also presented at a Neuroscience evening at the HR MacMilllan Space Centre and got to see some of the images I had made projected onto the planetarium dome! I love showing my research to people and rediscovering how cool it is through fresh eyes.

What kind of mentorship/guidance would be helpful for you at this stage in your career?

I am always interested in the trajectory other scientists take through their career and life. Academia is a unique career path which, from what I have seen, can be exciting, busy and require a lot of moving to new countries. I would love to hear from a range of different scientists how they found each career stage, and how they managed the demands of family, living somewhat nomadically and work-life balance. Tips for PhD students from people who have been through it are also always good!

“A science degree can open up many doors”

Nicole Janzen

Lab Manager

When did you know you wanted to be a scientist?

I first became interested in science when my science-teacher father showed me the periodic table. It seemed so neat and logical. I ended up taking chemistry in university but once I completed my first course in immunology, I found my interests definitely leaned towards the biology side of things.

Tell us about your career.

I started in Toronto at the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research (now closed) where we worked on the effects of high fibre diets on cancer. From there, I moved out to Vancouver where I applied for a job at The Biomedical Research Centre, which later became a part of UBC. I have now worked at UBC in three different laboratories in the fields of immunology and neuroscience.

Have you faced any challenges as a woman in science? If so, how did you deal with them?

As in many careers, there never seems to be a good time to have children. A typical career path in science includes a PhD, followed by a post-doctorate or a number of post-doctorates, and then finally, fourteen or so years later, you are ready for your dream job in science. As many jobs in science depend on building up your CV, taking time off in the middle or at the end of your schooling can be devastating to your career.

What’s your favourite thing about being a scientist?

Every day is different. You are not stuck behind a desk and the most exciting days are when you finally finish the data analysis and find out if you have statistical significance between your groups.

What sort of mentorship or guidance have you been able to offer to younger women thinking of careers in science or engineering?

I have now worked with more than 40 graduate students, and even more volunteers. Many students I have met in the lab had aspirations of becoming professors. Unfortunately, there are very few professor positions available. Although I cannot take credit for their choices, I have pointed out to them that a science degree can open up many other doors and some of these students have gone on to become a lawyer (specializing in patent law), a genetic councillor, and a project manager, just to name a few.

If you could go back in time and give your younger self some advice for your career, what would it be? OR What advice would you give to young people just starting out in their science careers?

Stay current. Novel procedures and equipment are developed every day that may better answer your question in a more specific and elegant manner. Many of the procedures I learned in the past are rarely used today (like Southern blotting).

“It’s important to recognize when you’re doing something to be ‘nice'”

Amanda Lee

Research Assistant

When did you know you wanted to be a scientist/researcher?

I started working as a research assistant in a behavioural neuroscience lab during the 3rd year of my BSc degree at UBC. Although I enjoyed working at the bench on pre-clinical experiments, I didn’t seriously consider integrating research into my future career. However, in my senior year I began working with participants for different research studies in physiology and clinical psychology. I found it incredibly rewarding to learn how to identify a knowledge gap or problem, incept a novel project to address that issue and observe the positive impact that your ideas can have on someone’s quality of life.

Tell us about your career/studies so far.

Near the end of my BSc, I worked in four different research facilities to get a better sense of the type of research I enjoyed most. I did a mix of pre-clinical work (animal models of spinal cord injury and cognition) and clinical research (neuroimaging and behavioural studies). After getting over mild commitment issues, I embarked on an MSc in Experimental Medicine under Dr. Andrei Krassioukov’s supervision at ICORD on the topic of breastfeeding and motherhood after spinal cord injury. I defended my MSc thesis and have since continued to work as a clinical research coordinator with Dr. Krassioukov on several projects. Right now, I am in the midst of interviews for medical school and very excited for the next step.

Have you faced any challenges as a woman in science/medical research? If so, how did you deal with them?

I have been fortunate to be lifted up by excellent peers and supervisors, who have never made me feel less valuable or competent than male counterparts. They are not only advocates of female representation in science, but also highly attuned to the challenges faced by women in STEM. I know this is certainly not everyone’s experience, so their support emboldens me to share challenges or discomfort I have experienced in other situations. One conference stands out to me: I was chatting with several graduate students when we were approached by a prolific and senior scientist. Despite introducing myself at the beginning of the conversation, he proceeded to ask each of the male graduate students about their research topics but never acknowledged me. Even while directly facing me, he passed over me to address the next male student beside me. I shared my frustrations with colleagues who listened, commiserated and encouraged me to speak up if a similar interaction happened in the future.

What’s your favourite thing about being in this field?

One of my favourite aspects of science is its collaborative nature and the unique projects that stem from creative, impactful partnerships. I’ve especially enjoyed taking a completely different perspective when approaching a topic, learning new skills and travelling in the name of discovery.

What sort of mentorship or guidance have you been able to offer to younger women thinking of careers in science?

I’m still in the early stages of scientific training, so I find myself more suited to the receiving end of mentorship. However, to younger female students I emphasize the importance of recognizing when you are doing something out of an obligation to be “nice” – even when your professional barriers are being compromised. A lot of us have been socialized as little girls to be polite and agreeable. This makes it harder to speak up and disagree with unreasonable requests, subtle acts of discrimination or gender-based inequity in the workplace. Having understood these pressures myself, I am happy to share my experiences and reflect with students on their own.

What kind of mentorship/guidance would be helpful for you at this stage in your career?

I tend to feel most motivated and inspired when I am preparing for “the next stage”, whether it is the next degree, career move or personal milestone. Over the past few years, my perspective has changed and I’ve learned that life happens neither linearly, nor in perfect phases. I’m really interested to hear from female physician-scientists who took unique routes to clinical practice in their desired specialties. I’d love to hear about unexpected challenges and strategies for successfully balancing research, medicine and life in general.

“I focus on doing good work, and let the work speak for itself”

Dr. Lyndia Wu

Dr. Lyndia Wu

Principal Investigator and Assistant Professor

When did you know you wanted to be a scientist?

Towards more senior years of graduate school is when I decided I would enjoy pursuing independent research in an academic setting.

Tell us about your career and journey to becoming a PI.

I actually applied to UBC in the last year of my PhD at Stanford and got an offer prior to graduating. Then I did a short one-year postdoc at Stanford then started my position at UBC. As a Canadian I am happy to come back to work in Canada, and UBC offers many opportunities for collaboration. I also love Vancouver!

Have you faced any challenges as a woman in science? If so, how did you deal with them?

Yes, there were times in my research career when I felt that opportunities were not fairly offered, or assessments were not fairly made, perhaps given my gender. I have learned that while we as women tend to say yes and compromise, we should look out for ourselves and push back when necessary. Also, I just put my main focus into doing good work, and let the work speak for itself.

What’s your favourite thing about being a scientist?

Having freedom in deciding research directions, and working on projects that could be translational.

What sort of mentorship or guidance have you been able to offer to younger women thinking of careers in science or engineering? And/or alternatively, have any female mentors help shaped your scientific career?

I have hosted a number of female students in the lab and would like to continue offer opportunities to female students interested in research. I have definitely seen many strengths in women in engineering and think that young women should be more confident that they can also do very well in a science and engineering career. My own postdoc supervisor was an accomplished professor in the male-dominated field of electrical engineering, and she gave me many tips on succeeding as a female faculty member in engineering.

If you could go back in time and give your younger self some advice for your career, what would it be? What advice would you give to young people just starting out in their science careers?

Read more papers and get inspired!

Thanks to UBC Work Learn student Jocelyn Chan for her hard work on this project. Jocelyn is in the third year of her BSc in Integrated Pharmacological and Physiological Sciences, and helps with social media and communications for ICORD.